Charlie Brown Jazz II

In 1964, Charles Schulz had been drawing Peanuts for 15 years. The strip had grown beyond its rudimentary situations and characters, when the children still acted like children and Snoopy acted like a real dog. Now the children were still children, they ate candy bars and went to the movies and played baseball, but while they were doing it they would contextualize their activities by discoursing on philosophy, mental health, and the nuances of religion. Instead of selling mud pies on the side of the road they were selling psychiatry.

Schulz had already been approached several times by Hollywood producers seeking to make an animated Peanuts film or television series, but he had turned them all down. Peanuts was on a rollercoaster of popularity at that point and merchandise was being produced as quickly as it could be approved. And for every item that was produced there were at least ten being turned down: Schulz insisted on personally approving every way his characters were merchandised.

But that year Schulz was approached by producer Lee Mendelson about creating a documentary about Schulz and the creation of his strip. Schulz had enjoyed Mendelson’s previous documentary on one of his heroes, Willie Mays, and agreed to meet with Mendelson. The following year Mendelson produced a short documentary on Schulz, notable for two reasons: short cartoons created by Schulz’s friend Bill Melendez, who had already created several animated commercials for Ford Motors, and the score composed by rising jazz star Vince Guaraldi.

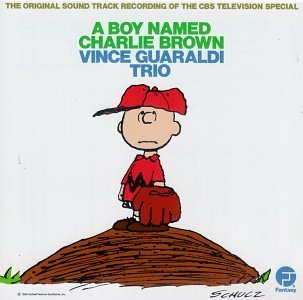

The documentary never aired. The soundtrack was collected onto an album titled A Boy Named Charlie Brown by the Vince Guaraldi Trio, and was a modest success. The animations were noticed by Coca-Cola, but rather than sponsor the documentary they were more interested in producing a Peanuts Christmas special. It was that show that established the Peanuts television specials as a television institution; a second soundtrack album by Guaraldi expanded on many of the same themes as Charlie Brown and permanently grafted his music to the animated Peanuts.

But it was A Boy Named Charlie Brown that introduced the themes that were to recur during the next decade of Peanuts animated specials, mostly character themes for the principal characters: Charlie Brown has two themes himself, and another for his constant utterance, Good Grief. There is a theme for Baseball, for Schroeder, even for Freida, the girl with the naturally curly hair. The Freida theme was almost never used in conjunction with her character, and instead popped up during a bit of mischief or humor, including one scene where Linus, lollipop in hand, destroys a pile of dry leaves freshly raked by Charlie Brown. His lollipop covered by leaves, he advises Charlie Brown: “never jump into a pile of leaves with a wet sucker.”

By far the most famous tune to emerge from the album is the one most closely associated with the Peanuts specials: the theme of the siblings, Linus and Lucy. It’s a rambunctious and rowdy piano tune, threatening yet funny, that thoroughly explored the dynamism in their relationship. It is commonly referred to today as the “Peanuts Theme,” perhaps because its the catchiest, or perhaps because by encompassing two of the four strongest personalities, (Charlie Brown, Snoopy, Linus and Lucy) much of the group dynamic was already captured. Regardless, it remains the most recognized and covered tune Guaraldi ever comitted to tape, a jazz standard.

Its effectiveness in musically portraying the two characters can be seen in the beginning of It’s the Great Pumpkin, Charlie Brown, where Linus and Lucy set out to find a jack o’lantern. After Lucy finds the largest pumpkin poor Linus could possibly carry, they head for home. When Linus comes to a hole in the fence the pumpkin couldn’t possibly pass through, he decides to roll it home, happily pushing the pumpkin along until he realizes it’s out of control, and desperately tries to stop it. When he hurts himself in the process, Lucy shows only irritation, and takes the pumpkin into the house herself. Once inside she pulls out a giant knife and starts scooping the pumpkin guts out. Linus wails to Lucy, “you didn’t tell me you were gonna kill it!” All to the beat of that irresistibly catchy tune.

Compared to the bustle of Linus and Lucy Charlie Brown’s themes are very plain and quiet. It’s no wonder the former tune took off to become the most recognizable theme, Charlie Brown’s theme is best suited to epilogues and fadeouts, not to kick off the ride. Charlie Brown’s success in real life has always been similar to his role in his cartoon life: his plain personality relegates him to the background, despite that he is a superstar.

There are all-encompassing tracks as well, like the appropriately solemn and introspective track Happiness Is, named for the recurring Peanuts theme that spawned a short book, Happiness is a Warm Puppy. In Peanuts, happiness wasn’t so much felt as it was sought and analyzed.

The other encompassing theme, Baseball, seems more at task to capture the game itself, certainly a worthy endeavor, but unfortunately unconcerned with Schulz’s conception of baseball and how he used it narratively. For Schulz, the baseball diamond was a place of discussion, of philosophy, religion and ideas, and also a place of deep, persistent loss. The tune comes off as more “take me out to the ballgame” than really capturing what a consistent disappointment the baseball games were to the children. In Guaraldi’s defense, Schulz was still developing the baseball device at the time. Regardless, this tune was probably a bit too complex to ever catch on as the main theme, despite its inclusion of all the characters.

The most noticeable absence from this collection is Snoopy, who has no music of his own. The album was recorded in 1965 when the strip was more driven by the group dynamics of the children than Snoopy’s fantasy life. That side of the strip was only beginning to emerge, and it would be a year before Snoopy donned his flight cap in pursuit of the Red Baron. But in subsequent years more music would be written for Snoopy than any other character, and many that were suited for him alone, including the second most famous tune of the specials: Joe Cool.

The album features several other tracks that work better as stand-alone jazz compositions than accompaniment for the Peanuts cartoons. This isn’t particularly surprising considering that Guaraldi’s Peanuts work was reminiscent of a sound he had already developed over the first half of his career, most notably in his biggest hit, Cast Your Fate Into the Wind, which could easily have appeared in any number of Peanuts specials.

Following the completion of A Charlie Brown Christmas, Guaraldi’s work was dominated by producing for the subsequent Peanuts specials, and he contributed the music for the next fifteen specials before his untimely death at 47. The final Peanuts special he contributed to was It’s Arbor Day, Charlie Brown, which aired on March 16, 1976.

So where’s the rest of the music? Only two albums for fifteen specials, and they were for the first two shows? Well, actually there were three. Until recently. I’ll dive into all that next time.

References:

The Peanuts Animation Page

Vince Guaraldi Biography from the Peanuts Collectors Club

Peanuts Timeline

The Official Vince Guaraldi Site